Since the days of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, the far right have presented themselves as the defenders of free speech. Mosley argued that free speech was almost non-existent due to violent Marxists and that his paramilitary forces were the only thing defending free speech in Britain. Despite many politicians and journalists arguing that Mosley should be debated, he complained that there was a conspiracy to silence him. Recent rhetoric by the far right has a history going back to the 1930s and it is one that we should be wary of. The following is based on an excerpt from my book project on the history of ‘no platform’.

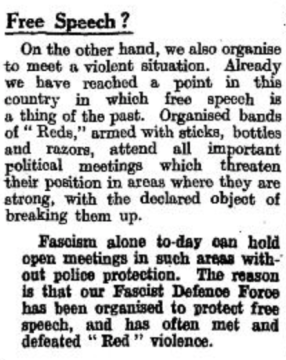

Since the days of the British Union of Fascists (BUF), the far right in Britain have attempted to portray themselves as the defenders of free speech. As meetings of the BUF were interrupted by anti-fascist activists, the BUF complained that ‘the Reds’ were trying to deny them their freedom of speech. In the first issue of The Blackshirt from February 1933, Oswald Mosley’s front page article, quoting from the BUF’s 1932 manifesto The Great Britain, claimed that the anti-fascist campaigns against the newly established BUF had indicated that ‘we have reached a point in this country in which free speech is a thing of the past’.[1] Mosley complained:

Organised bands of “Reds,” armed with sticks, bottles and razors, attend all important meetings which threaten their position in areas where they are strong, with the declared object of breaking them up.[2]

Only the fascists, Mosley claimed in his newspaper, could ‘hold open meetings in such areas without police protection’, suggesting that the reason for this was that the ‘Fascist Defence Force has been organised to protect free speech’ which had ‘often met and defeated “Red” violence’.[3] From the very beginnings of the BUF, Mosley embraced militarism and violence as part of his political movement, with the Fascist Defence Force being used as a ‘shocktroop’ to confront anti-fascist opposition.[4]

The trope of the far right being silenced by left-wing violence, which continued across the twentieth century and into the present, was first used by Mussolini and Hitler in the 1920s and explicitly used again by Mosley in the 1930s. The portrayal of the paramilitary Fascist Defence Force as an organisation built to forcefully respond to the threats from the left indicates the early embrace of violence in the BUF, confident of its own strength and not needing to rely on the police. It was only after the disturbances at Olympia in June 1934 that the BUF moved to explicitly calling for the police to intervene against anti-fascist activists.

These were continued themes in the BUF propaganda throughout the 1930s. In the 1936 publication Fascism: 100 Questions Asked and Answered, Mosley made a distinction between indoor meetings, where BUF stewards were allegedly allowed ‘to preserve order in accordance with the Law’, which meant ‘[i]f the Chairman orders the removal of a persistent interrupter, it is [the stewards’] duty to eject him with the minimum of force necessary to secure his removal’[5] – even though it was evident from disturbances at Olympia and elsewhere that the BUF did not use ‘the minimum of force’ and brutally beat a number of hecklers. On the other hand, Mosley stated that for outdoor meetings, ‘it is the duty under the Law of the police alone to preserve order, and Fascists do not attend for that purpose’.[6] However various clashes between fascists and anti-fascists on the streets show that the BUF did not leave the police to preserve order.

In March 1936, Mosley asserted that when the BUF first emerged just over three years earlier, ‘free speech in Britain had virtually come to an end’.[7] He complained that in Britain’s industrial cities, ‘Socialism could not be vigorously attacked from the platform without the break-up of the meeting by highly organised bands of hooligans.’[8] For Mosley, the BUF were the antidote to this alleged socialist intimidation.

He declared that the Blackshirts ‘with their bare hands’ had ‘overcome red violence armed with razors, knives and every weapon known to the ghettoes of humanity’, and thus pronounced, ‘Their bodies bear the scars, but free speech is regained’.[9] Once again, Mosley portrayed the BUF as the defenders of free speech against communist violence and suggested that it was only through violent self-defence that free speech was preserved.

Mosley complained elsewhere that the BUF were hindered in their pursuit of free speech by the government and the police who increasingly prevented BUF rallies and marches from occurring out of fear of violence. A few weeks after the ‘Battle of Cable Street’ in late 1936, Mosley lamented in BUF weekly Action that the government did not use the law ‘to deal with the assailants [ie the anti-fascist activists] but with the defenders of Free Speech’, objecting:

If trouble takes place at a meeting, Government and law now regard as the guilty party, not those who assemble with violence to prevent an opinion being stated, but those who peacefully assemble to state that opinion.[10]

However Iain Channing has argued that the opposite was often the case, writing that ‘it appears more common that it was audience members who heckled and showed their contempt for fascism to end up before a magistrate.’[11]

Elsewhere in their propaganda, the BUF argued that ‘freedom of speech does not exist’ and seemed nonplussed to actually hold up this freedom, especially if they came to power.[12] Mosley suggested that while ‘anyone can carry a soap box to a street corner and… make any moderate noise that he sees fit to emit’, there was no ‘effective action following from his words’.[13] In the eyes of Mosley, only the press and the party machine had a voice and wrote, ‘in actual practice under this system freedom of speech is the freedom to be the servant of the financier.’[14] While the BUF claimed to be defenders of freedom of speech, the BUF programme envisaged ‘freedom of speech’ to be accessed via Corporate Life, the alleged ‘machine for putting into practice the principle of freedom of speech’.[15] Mosley’s convolutedly explained this process in Action in 1936:

Every man and woman with any industry, profession, or interest in this country will be able to enter into the work of his or her corporation. There they will not only be permitted but invited to express their opinions. The ordinary man and woman drawn from the great majority, who cannot or do not care to talk at street corners, will be invited to express their opinion. They will be encouraged to do so because the expression of their opinions will affect the work of the Corporation, and through that definite machinery the opinion of the people will affect Government.[16]

So even though the BUF stressed the idea of free speech when discussing their public meetings and claiming that anti-fascists threatened their freedom of speech, the BUF did not foresee in their programme any freedom of speech outside the fascist corporate state.

This reinforced the idea for the Communist Party and other anti-fascist activist that the real threat to free speech and democracy was fascism, with them pointing to what had happened to the working class, trade unions and socialists in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Arguing against the BBC giving airtime to Mosley, the Daily Worker put that ‘Fascism is the same in all countries – there is no special British brand – it is a creed of murder and violence’.[17] Then in 1937, discussing the fascist breaking up of a Labour Party meeting being addressed by Clement Atlee, the same paper stated:

Fascism, wherever, and in whatever form it raises its head, aims to destroy free speech, democracy, and every liberty which centuries of working-class endeavour have wrestled from the ruling class.[18]

The Communist Party lambasted the Labour Party for its pleas of allowing ‘free speech’ for Mosley and the BUF. For example, the Daily Worker criticised the short-lived Labour MP Fielding West for writing to the Daily Herald that ‘the Labour Party do not fear the effect of Mosley’s speeches. In any event, let him be heard, for free speech is still precious to-day’.[19] The Communist newspaper retorted that ‘[w]hile even Tory MPs were horror-stricken at the brutalities of Mosley, this Labour MP comes out attacking the Communists and pleading with the workers to give freedom to Fascism.’[20] The following month, Rajani Palme Dutt wrote in Labour Monthly that the Labour Party leadership was too ready to defend the bourgeois concept of ‘freedom of speech’, but explained that this meant:

the workers must listen like docile, obedient sheep in regimented silence whenever a noble, respected bourgeois chooses to get on his hindlegs to air his caste-theories and generally put them in their place.[21]

Dutt claimed that ‘freedom of speech’ was allowed for proponents of ideologies that sought to inflict violence upon the working class, but often trade unionists and socialists were denied freedom of speech and on occasions, charged with sedition.[22] To prevent Britain allowing a fascist movement to rise, like in Italy and Germany, meant practical opposition to Mosley and this meant opposition to Mosley’s ability to broadcast his message in public.

[1]The Blackshirt, 1 February, 1933, p. 1.

[2]The Blackshirt, 1 February, 1933, p. 1.

[3]The Blackshirt, 1 February, 1933, p. 1.

[4]Stephen Dorril, Blackshirt: Sir Oswald Mosley and British Fascism(London: Penguin 2007) pp. 189-190.

[5]Oswald Mosley, Fascism: 100 Questions Asked and Answered(London: BUF Publications, 1936) p. 56.

[6]Mosley, Fascism, p. 56.

[7]Mosley, Fascism, p. 57.

[8]Mosley, Fascism, p. 57.

[9]Mosley, Fascism, p. 57.

[10]Action, 24 October, 1936, p. 9.

[11]Iain Channing, ‘Blackshirts and White Wigs: Reflections on Public Order Law and the Political Activism of the British Union of Fascists’ (University of Plymouth: Unpublished PhD thesis) p. 170.

[12]Oswald Mosley, Tomorrow We Live(London: BUF, 1938) p. 20.

[13]Mosley, Tomorrow We Live, p. 20.

[14]Mosley, Tomorrow We Live, p. 21.

[15]Mosley, Tomorrow We Live, p. 22.

[16]Action, 24 October, 1936, p. 9.

[17]Daily Worker, 11 June, 1934, p. 3.

[18]Daily Worker, 28 September, 1937, p. 5.

[19]Cited in, Daily Worker, 11 June, 1934, p. 3.

[20]Daily Worker, 11 June, 1934, p. 3.

[21]Dutt, ‘Notes of the Month’, Labour Monthly, July 1934, pp. 398-399.

[22]Dutt, ‘Notes of the Month’, pp. 399.

Leave a comment