Yesterday Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced that if the Senate did not pass two pieces of legislation to re-establish the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC), he would call for the Governor-General to issue the writs for a double dissolution election. This would mean that all seats in both the House of Representatives and the Senate would be contested at the election to be held on 2 July. Only a handful of double dissolution elections have occurred sine Federation in 1901, with the first double dissolution called by a Liberal Prime Minister occurring in 1951, requested by Sir Robert Menzies.

Menzies had won government in December 1949, defeating Ben Chifley’s Labor government, which had been in power since the end of the Second World War. The Liberal-Country Party coalition had made significant gains in the House of Representatives, but Labor still controlled the Senate, which made the passing of controversial legislation difficult, especially as a central part of the LCP’s programme in the lead up to the election was the proposal to ban the Communist Party of Australia (CPA).

The CPA had been briefly banned during the war while Menzies was Prime Minister, but this was reversed by Chifley’s predecessor, John Curtin. As the Cold War erupted in the late 1940s, the CPA took a particularly militant line, partially inspired by the rise of communism in Asia and assertion by the Soviets that the world was falling into two opposing camps – the democratic and ant-fascist bloc of the Soviet Union and the Eastern European ‘People’s Democracies’ (soon to be followed by China) and the anti-democratic and fascist bloc of the Western nations. This led to fierce battles in the Australian labour movement over its stance towards Chifley’s Labor government, with the CPA-led trade unions pushing for confrontational industrial militancy in several industries. This came to a head in 1949 with the Coal Strike that led to the Chifley government ordering troops to break the strike and the imprisonment of several Communist trade unionists.

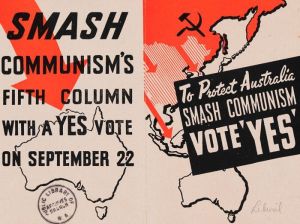

This industrial unrest gave Menzies the opportunity to campaign on the programme that an LCP coalition would ban the CPA. Drawn in tandem with the Suppression of Communism Bill by the Malan government in apartheid South Africa, the Menzies government drafted the Communist Party Dissolution Bill in early 1950. First introduced into the House of Representatives in April 1950, the Bill was opposed by Labor and heavily criticised outside of Parliament by the Communist Party and a significant portion of the trade unions. Initially rejected by the Labor controlled Senate, Menzies threatened a double dissolution election and Labor senators, possibly against the public statements made by Chifley, passed the Bill into law in October 1950. The legislation banning the CPA was broad in its scope and meant that fellow travellers who sympathised with Soviet communism could be prosecuted, as well as ‘official’ members of the Party.

As soon as the Bill became law in November 1950, it was subject to a High Court challenge by the Communist Party and several trade unions, with H.V. Evatt (soon to be Labor leader) acting as one of several counsels for the trade unions in this case. On 9 March, 1951, a 6-1 majority of the High Court of Australia found that the Communist Party Dissolution Act was unconstitutional and its powers to prosecute individuals for their alleged connection to the CPA violated what could be included in Commonwealth legislation. To re-introduce legislation banning the CPA would need a change to the Constitution, which itself needed a referendum to allow these changes. Without control of the Senate, Menzies felt that he would be unable to pass the necessary legislation to alter the Constitution and subsequently, formally ban the Communist Party of Australia.

On 15 March, 1951 – a week after the High Court’s decision – Menzies formally requested that the Governor-General order a double dissolution election, on the grounds that the Labor controlled Senate had already twice rejected his Commonwealth Bank Bill. Two days later, both houses of Parliament were dissolved and a bicameral election was held on 28 April, 1951. While Labor gained five seats in the House of Representatives, Menzies won control of the Senate and now had a majority in both houses.

This allowed the Menzies government to introduce legislation that would start the process to change the Constitution that would render any new Bills to ban the Communist Party legal and without grounds to challenge. With control of the House of Representatives and the Senate, the Menzies government quickly passed the Constitution Alteration (Powers to Deal with Communism and Communists) 1951 Act and a referendum was held on 22 September 1951.

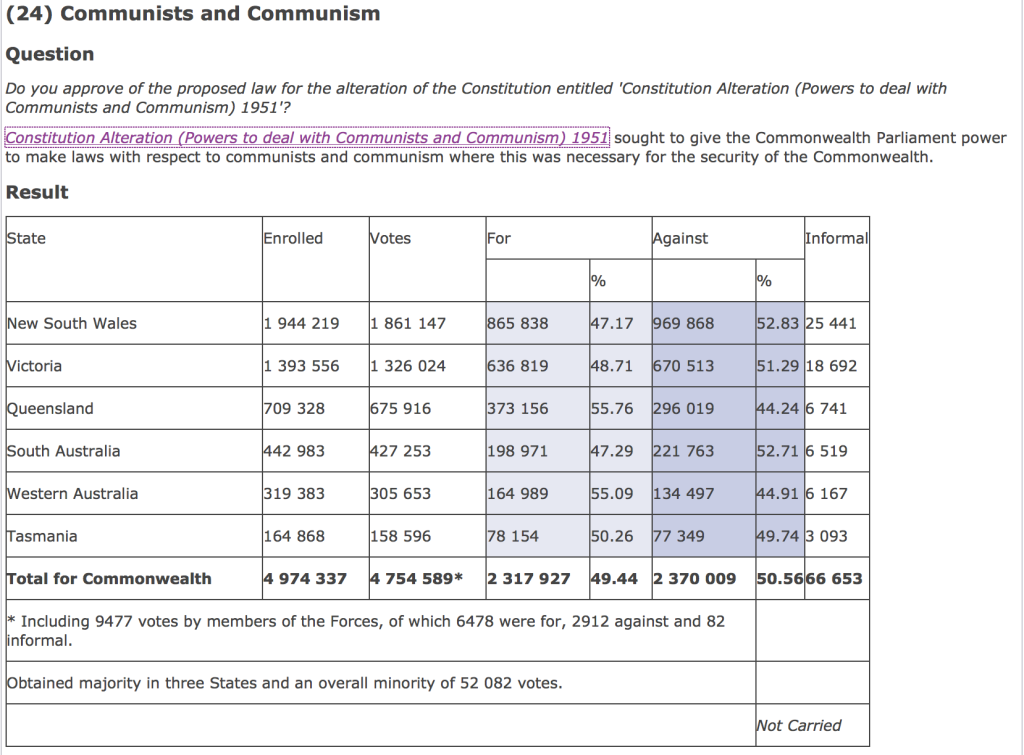

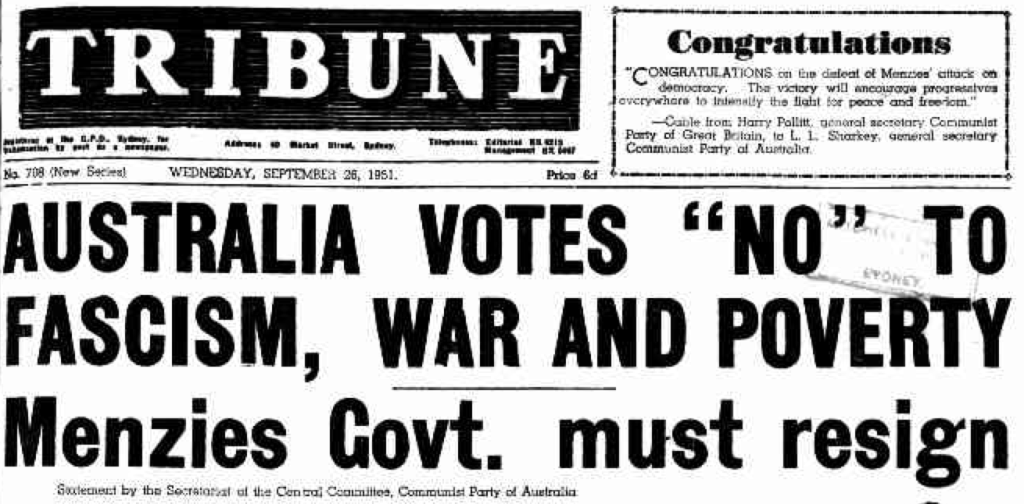

As the above graph shows, the states of New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia voted ‘no’ and at the federal level, a slight majority voted against altering the Constitution to allow the banning of the CPA. While the gamble of the double dissolution had paid off for Menzies, his attempt to change the Constitution to ban a specific political organisation failed and was seen as government over-reach by many commentators.

Since Menzies, there have only been four double dissolutions, by Gough Whitlam in 1974, by Malcolm Fraser (in caretaker mode) in 1975 and 1983, and by Bob Hawke in 1987. Each time the incumbent government, besides Fraser in 1983, has retained power – although in the case of Whitlam, only briefly. It could be argued that powerful political conviction on a controversial, yet important, topic has helped governments get over the line in double dissolution elections. The question is whether the Turnbull government have this conviction or the right issue to take to the electorate if they proceed with a double dissolution.

Leave a comment