The protests against Eric Kaufmann at the University of Bristol last week are part of a much longer history of ‘no platforming’ at the university, stretching back to the 1980s.

This research is part of a book that I am writing on the history of ‘no platform’ and free speech at British universities for Routledge’s Fascism and Far Right series.

Last week students at the University of Bristol staged a walkout in protest of a talk being given by Professor Eric Kaufmann, who has been promoting his book Whiteshift about white anxieties about immigration. Denigrating ‘the cultural Left’ for their support for multiculturalism, Kaufmann has argued for ‘ethno-traditional nationhood’, with ‘slower immigration to permit enough immigrants to voluntary assimilate into the ethnic majority, maintain the white ethno-tradition’.[1] Umut Ozkirimili has described Kaufmann as part of the ‘academic alt-right’,[2] while Alana Lentin argues that Kaufmann ‘confuses racial self-interest expressed as white opposition to immigration with the sense of ethnic belonging’.[3] By doing so, Lentin writes, Kaufmann attempts to portray white concerns about immigration as ‘not racism’, but legitimate fears.[4]

Kaufmann was invited by the Centre of Ethnicity and Citizenship at the University of Bristol to speak about his research. The Bristol Post reported that around 30 students walked out of the lecture, but some who opposed Kaufmann also stayed.[5] Several academics at the university questioned why Kaufmann was invited. On twitter, Kaufmann complained that a ‘small, vocal minority’ had the potential to ‘no platform’ his event and while acknowledging that they did not actually shut down the event, he asked whether there should penalties ‘in order to deter such actions in the future’.[6] A number of people argued that those who walked out were merely demonstrating their freedom of speech to not listen to Kaufmann, who has been championed by free speech absolutists recently. This has been part of a broader debate about free speech, ‘no platforming’ and the ‘marketplace of ideas’ in an era of a global right-wing resurgence.

The recent media obsession with ‘no platform’ and free speech at British universities (also seen in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand) often overlooks the history of these debates and the lengthy development of the tactic of ‘no platforming’ since the 1970s. Many commentators are quick to blame the use of ‘no platform’ tactics on the rise of ‘identity politics’, suggesting that it is a twenty-first century phenomenon. But ‘no platform’ has been official NUS policy since 1974 and there have confrontational protests with conservative and far right speakers at British universities since the late 1960s.

This incident at Bristol University in 2019 echoes a much longer history of battles over free speech at the university. In particular, the university became a significant site of student protest against speakers perceived to be racist in the mid-1980s. This happened amidst a wave of Conservative MPs and hard right speakers visiting universities that provoked strong student reactions and led to the Thatcher government introducing legislation seeking to protect ‘free speech’.

Throughout the year 1986, the University of Bristol was a focal point for the debate between ‘no platform’ and ‘free speech’ on campus. There seemed to be a significant increase in the number of protests against visiting MPs to university campuses between 1985 and 1987, with several notorious hard right Tories, as well as other figures on the right (such as Enoch Powell) attempting to speak on campuses throughout this period. By 1985, students had been locked in a four year battle with the Thatcher government over funding for higher education, with cuts to student grants and plans to introduce fees for higher education.[7] As Richard Aldrich has written, ‘the more market-led, free-enterprise approach to society and the economy which characterized the premiership of Margaret Thatcher’ influenced the education reforms of the 1980s,[8] which led to confrontations with students, just as the government had in their battles with other sections of society such as the trade unions, peace campaigners or Britain’s ethnic minority communities. The period of confrontation with MPs on campus came at the end of the Miners’ Strike, which had polarised British society and generated a strong oppositional movement to the Thatcher government.

In January 1985, Enoch Powell cancelled a visit to the University of Leeds after the students declared that they would protest against him[9] and Home Secretary Leon Brittan faced a hostile crowd at the University of Manchester in March 1985 in the week that the Miners’ Strike ended.[10] At the University of Bristol, a Professor of Modern History, John Vincent, became a target for protesting students who objected to his columns for The Times and The Sun. Vincent was considered part of a cohort of ‘new right’ intellectuals, who ‘skilfully adapt[ed] the cultural racism of the “New Right” circles into a populist format’, namely the mainstream press.[11] Vincent had written some inflammatory columns for The Sun, such as one in July 1985 in which he blamed the death of a black toddler on Lambeth Council’s belief in ‘separate treatment’ for black people.[12] Cited by Paul Gordon, ‘The anti-racist “mumbo jumbo about black identity”, Vincent wrote, had overridden the safety of the child and had led to disaster’.[13]

A campaign to boycott Vincent’s lectures started in 1985 and escalated in early 1986, coinciding with the beginning of the Wapping Strike, when Rupert Murdoch moved his printworks and instigated a long-running battle with several trade unions (months after the Miners’ Strike ended). In late February 1986, students disrupted a lecture by Vincent and this was repeated the following week. The Daily Telegraph described the second incident:

Prof. John Vincent… was escorted by police through a mob of angry students yesterday after giving a lecture at Bristol University.

Mr Vincent… left the arts faculty building after a two-hour siege by about 300 students while he gave a history lecture abandoned last week due to protests.[14]

The newspaper cited the University’s Information Officer who claimed that the protest was ‘orchestrated by the Socialist Workers Party and anarchist elements determined to widen the dispute over the printing of Mr Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers at Wapping’.[15]

The disruption of Vincent’s lectures was condemned in the media. An editorial for The Times declared:

An academic lecture has an absolute privilege. Disruption is an act of intellectual vandalism as dangerous as any other effort to truncate learning and the exchange of opinion…

Professor Vincent’s extra-curricular activities are irrelevant. Prveenting his teaching about late nineteenth century politics was to disrupt the instrument of higher education itself, the academic lecture.[16]

In the same newspaper, Lord Beloff stated that the disruption of lectures due to the lecturer’s external activities ‘must be regarded as conduct so irreconcilable with the idea of a university that its perpetrators must, after due warning, face expulsion’.[17]

15 students originally faced disciplinary proceedings as a result of the disruptions,[18] but this grew to 19 by May 1986, when nine were acquitted, two hard the charges against them dropped and seven were found guilty.[19] Baroness Cox, during parliamentary debates about the introduction of legislation to protect free speech on campuses, complained that the penalties for those found guilty were too mild.[20] John Carlisle, an MP who faced violent protests on various campuses around the same time, also criticised the leniency shown to the protesting students. In the House of Commons in June 1986, he said:

The students who came before the court were merely fined and slapped on the wrist. They were not expelled from the university. The taxpayer has the right to ask whether such students should be able to continue their studies at the taxpayers’ expense when they are intent on disrupting meetings.[21]

Eventually the seven students who were found guilty had their convictions quashed on a technicality.[22] Meanwhile John Vincent took a leave of absence from his teaching role after the disruptions, but continued to write.

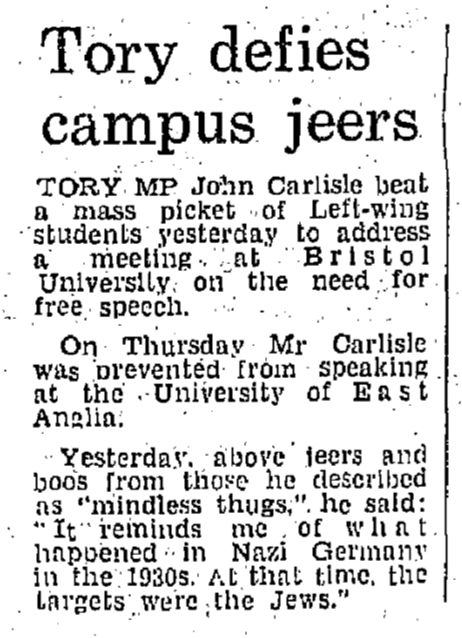

But the troubles didn’t stop after this. In late April 1986, Conservative MP John Carlisle visited Bristol University as part of his tour of university campuses. Carlisle was a prominent member of both the Monday Club and Federation of Conservative Students, and was a hard right figure within the Conservative Party. In the 1980s, he was most well-known for his support for apartheid South Africa and his condemnation of the African National Congress, including the imprisoned Nelson Mandela. Matthew P. Llewellyn and Toby C. Rider have described Carlisle as a ‘fierce pro-Pretoria spokesman’[23] and it was on this topic that he frequently spoke at public meetings, including at universities. In February 1986, large student protests had forced Carlisle to cancel speaking engagements at the University of Bradford and Oxford University as he faced hostile crowds. He pre-emptively cancelled a visit to Leeds Polytechnic the following week after these incidents. In late April, Carlisle went to the University of East Anglia, where there was a picket by some students (mostly aligned with the SWP) and a much larger ‘silent vigil’.[24] Carlisle managed to bypass the crowd, but his speaking engagement was eventually cancelled.[25]

A day later, Carlisle arrived to speak at Bristol University, invited by the Conservative Association. He was joined by fellow Tory MP, Fred Silvester, who had recently introduced a private members’ bill to ensure free speech on campus[26] – an idea that had been raised by Sir Keith Joseph’s green paper on higher education the previous year and would become part of the Education (no. 2) Act 1986 by the end of the year (after pressure from the House of Lords).[27] Unlike many of his previous attempts at speaking at universities that spring, Carlisle was able to address a crowd, despite significant student protests. The Times reported that ‘more than 100 left-wing students attempted to disrupt a meeting on free speech’ and that both MPs faced ‘a barrage of screaming, foot stamping and obscenities’.[28] The newspaper further described the protest with the following:

Ignoring cries of ‘fascist’ and ‘racist’, Mr Carlisle said he was pleased that in Bristol at least he had been allowed to address a meeting…

Making himself heard through a microphone in spite of a fire alarm being activated, Mr Carlisle shouted: ‘You won’t stop us because we believe in the fundamental principle of democracy’.[29]

Using the trope of the ‘red fascist’, Carlisle said that the reaction by the protesting students reminded him of ‘what happened in Nazi Germany in the 1930s’.[30] By the mid-1980s, the comparison between protesting students and Nazism was a well-worn allegory, often used (since the late 1960s) to portray students as violent or hostile to opposing ideas.

Over the summer, Carlisle became one of the staunchest proponents of legislation to be put in place to protect free speech at British universities and greater penalties for those who disrupted speakers. By the autumn of 1986, the section of the Education Bill regarding ‘no platform’ and free speech was being debated in parliament, which coincided with further clashes between hard right speakers and protestors.

In October 1986, Enoch Powell visited two universities amidst this debate and following in the footsteps of Carlisle and others. As Camilla Schofield has argued, Enoch Powell had an influence on the hard right forces in the Conservative Party that developed Thatcherism in the 1980s,[31] but during Thatcher’s Prime Ministership, Powell himself remained a critic on the right of Thatcher. He had left the Tories just prior to the 1974 election over the issue of British membership of the European Economic Community and joined the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP). As the ‘Troubles’ continued into the 1980s, Powell frequently spoke about the issue of Northern Ireland. The other major topic that Powell spoke on in the 1980s was ‘race relations’ and immigration, a topic that had originally brought him notoriety in the late 1960s. Powell used the 1980-81 and 1985 riots as vindication of his racist pronouncements on Commonwealth immigration and challenged Thatcher to clarify her position on non-white immigration in the wake of the 1985 riots.[32] Despite not being a member of the Conservative Party anymore, Powell was still a drawcard for the right and he was invited on a numberof occasionsto address Conservative Associations at various universities around the country. While he had to cancel a speaking event at Leeds University in January 1985 after a proposed protest, he had still spoken at Cambridge later in the year with little protest, but after the actions against John Carlisle at a number of universities, Powell’s campus visits drew a renewed level of opposition.

A week prior to his proposed speech at Bristol, Powell had had to abandon a talk at University College Cardiff (UCC at the time; now part of Cardiff University) when students from the Socialist Workers Student Society, as well as the UCC Labour Club, the UCC Women’s Group and the UCC Union of Liberal Students (several of which were leading members of the UCC student union),[33] launched a protest to prevent Powell from speaking. The front page of Gair Rhydd, the student newspaper at UCC, described the protest:

Trouble began almost before the meeting had started when Socialist Worker Students, angered at the prospect of the controversial right-winger speaking at UCC, mounted a picket outside room 22 of the Law building.

When this failed to stop the meeting they attempted to enter themselves… After ten minutes of argument [sic] most of the protestors were kept out.

Trouble flared up again, however, when Mr Powell began speaking. A group of protestors flung open the doors and occupied the platform on which Mr Powell stood. Mr Powell then faced a barrage of abuse and chanting of ‘No free speech for racists’…

As it became more and more obvious that the protestors had no intention of leaving until Mr Powell did, the UWIST College Secretary made an appeal to the demonstrators to stop chanting of face disciplinary action. He was unable to finish his announcement before being drowned out by further chanting.

Mr Powell then left with the words ‘Thank you for your courtesy’, and beat a hasty retreat to a waiting car.[34]

Ten students were eventually identified and faced disciplinary proceedings brought by the College, but the student union argued that the College had failed to inform the student union in a timely manner of Powell’s proposed visit.[35] The student union declared, ‘College denied us the right to organise and orderly protest… The spontaneous nature of the demonstration was due to College’s negligence.’[36] As protests against the disciplinary actions grew in the weeks that followed, the student union’s Communications Officer, Jake Lynch, claimed that the College had ‘ridden roughshod over the Unions [sic] No Platform policy’.[37] This disciplinary charges were dropped after a negotiated settlement between the student union and the UCC administration, which also led to a revised version of the ‘no platform’ policy at UCC.[38]

The week after the Cardiff incident, Powell was scheduled to speak at the University of Bristol, invited by the Bristol University Conservative Association. The student union at the University of Bristol did not have a formal ‘no platform’ policy in place (in fact a referendum on whether to introduce such a policy was being held during the Powell debacle) and the student union instead urged a silent protest.[39] Similar to when John Carlisle visited Oxford, Leeds and Bradford earlier in the year, the President of the student union, David Gottlieb, suggested that the Conservative Association was being provocative with their invitation of Powell.[40] Gottlieb queried the Conservative Association’s aims with their invitations, arguing that ‘the individuals who have invited these speakers to come and talk here in the sensitive atmosphere of Bristol must bear some responsibility’ for stoking tensions on campus.[41] He added, ‘It is my considered opinion that there are people in this Students’ Union whose actions prove them to be interested not in protecting freedom of speech but in stirring up trouble’.[42] An editorial in the student newspaper Bacus also questioned the motives of the Conservative Association in inviting Powell, asking:

Do they hope for interesting speeches, or for the sort of protest which will give Fleet Street the chance to run yet more ‘left wing thug’ stories?[43]

In a Union General Meeting leading up to Powell’s visit, Phillip Malcom, the Chairman of the Conservative Association, said to those opposing Powell’s invitation that he ‘would not be intimidated in defending free speech’, claiming to be ‘fanatically in favour of free speech’.[44]

Bacus also reported that the University were reluctant to intervene in the case, even though the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals had previously recommended that ‘speakers in possible danger should be barred’ (especially after the incidents involving Carlisle a few months prior), while the student union president stated that he did not expect any trouble from students regarding Powell’s visit.[45] The editorial in the student paper implored students to be peaceful in their demonstrations, pleading:

Any sort of violent demonstrations will discredit all opposition groups in the eyes of those who read such reports [from Fleet Street].

Don’t play into the hands of the Tories and right-wing press by resorting to violence.

We will suffer the consequences if you do.[46]

While around 200 students had attended a peaceful protest against Powell in the foyer on the building where Powell was speaking, a smaller group of protestors violently confronted Powell shortly after he began. The front page of Bacus described the incident:

Around 30 demonstrators, mostly anarchists from outside the University, gathered at the front of the hall hurling abuse and spitting at Mr. Powell. They blew whistles, let off stink and smoke bombs and at one point threw a ham salad sandwich at him…

Mr. Powell left the stage after only ten minutes when the protestors began shaking the crash barriers in front of the stage.

Three of the demonstrators then climbed onto the stage, overturned tables and chairs and snapped the microphone stand. Two of them gave mock Nazi salutes to the audience.

Others tried to chase Mr. Powell but were met by a locked door which one protestor kicked in.[47]

The actions by the anarchists were condemned widely. Phillip Malcom described the events as ‘worse than I could ever have imagined’ and called for legal action to be taken against those who disrupted Powell.[48] An editorial in Bacus declared that the anarchist protestors had ‘discredited everybody who had made an effort to provide a forum for those who find the views of Powell and his ilk abhorrent’.[49] In the Daily Express, Lord Chalfont called those who disrupted Powell ’a mob of illiterate morons’.[50] Even the SWP criticised the anarchists for their ‘tactical suicide’,[51] suggesting that ‘the event was marred by the Anarchists’.[52]

The anarchists themselves wrote to Bacus justifying their position. Alongside affirmation of the broader ‘no platform’ position shared by the SWP and others that ‘it should not be used as an inalienable right to allow a racist a platform’, the anarchists argued that ‘[s]ymbolic demonstrations do nothing to prevent racist attacks or the spread of racist propaganda.’[53] They rationalised their tactics by claiming:

In the absence of an effective anti-racist policy in this Students Union there was no other way of preventing Powell and what he represents from speaking.[54]

A week later, two figures from the ‘new right’ centred around the journal Salisbury Review, John Savery and Ray Honeyford, spoke at Bristol University, alongside John Bercow from the Federation of Conservative Students (FCS). The FCS had been involved in the invitations of Carlisle to the University of Bradford and to Leeds Polytechnic earlier in the year and many accused them on deliberately trying to provoke the student left into ‘no platforming’ by bringing these hard right figures onto campus to speak. The FCS campaigned against ‘no platform’ throughout the 1980s, often as part of a wider campaign against the ‘closed shop’ of the NUS.[55] Future Speaker of the House John Bercow debated the policy at the University of Leeds shortly before the FCS was disbanded in late 1986, arguing that the policy was ‘dangerous’ because ‘it enable[d] cowardly student unions to use the policy against any people to whom they object’.[56] When asked whether he would allow the NF to campaign on campus, Bercow said he would, but claimed that ‘No Platform is designed solely to exclude Conservative MPs’ (despite evidence that fascists were still active on campuses across the country in the early 1980s).[57]

For this event with Savery, Honeyford and Bercow, the student union had significantly increased security for the event in the light of the Powell protests, with Bacus reporting little trouble at the event.[58] Bercow commented on the disruption of the Powell speech the previous week, calling it ‘a disgrace to a free society and to the very concept of an academy where debate and free speech occur’.[59] The student newspaper stated that there only three hecklers inside the venue and once the event had ended, Honeyford was ‘jostled and pushed by about fifty demonstrators’.[60] One protestor attempted to throw yellow paint over Honeyford but missed, hitting a car, other protestors and a policeman.[61]

In the wake of these incidents at Bristol, the student union held a vote on whether a ‘no platform’ should be introduced at the university. According to Bacus, students were to vote ‘either to allow all freedom of expression within the law, or to ban organisations such as the National Front and the British Movement and their members’ (with the vote requiring support from 500 students to be binding).[62] However the NF and BM were not the target of the recent protests against Carlisle, Powell and Honeyford and the student union stressed that ‘[n]o platform would not be used to ban Conservative MPs unless they are declared members of the National Front or like organisations.’[63]

For the anarchists and Trotskyists who disrupted Vincent and Powell, whether a formal ‘no platform’ policy applied to Tory MPs was a moot point – the NUS endorsed ‘no platform’ policy at the national level made a distinction between fascists (who were to be ‘no platformed’) and hard right politicians (who were to be allowed to speak), but was often ignored by more militant protestors from the left. The Powell incident showed that disruptive protests happened outside the bounds of the politics of the student union, often at odds with the wishes of the student union itself. As one of the protestors wrote in a letter to Bacus:

When we sent [Harvey] Proctor, Vincent and Powell packing we were not simply silencing racists. We were saying an emphatic ‘No!’ to the lie that our ‘free speech’ has anything to do with real freedom or power over our own lives.

The right must continue spouting its cliches [sic], and in such a white and middle class university as Bristol it can be no surprise that so many are willing to swallow them at face value. But, make no mistake about it, the only freedom that the brats in BUCA really care about is the freedom to stay rich and become powerful, and that means that the rest of us must stay poor and powerless.

We can talk about it as much as we like. That’s our freedom of speech. Unless we back our words up with action nothing will ever change.[64]

An editorial for Bacus the week of the vote implored for a more civilised discourse around politics at the university, writing:

Whether we get No Platform or not, let common sense be the guiding instinct to those on both sides of the political divide. We do not want a repeat of the scenes at the Powell meeting…[65]

This was a sentiment expressed by moderate student union leaders and student newspaper editors across the country in the mid-1980s (and is something that is still mentioned today) – that the far/hard right and the far/hard left were at each other’s throats and left no room for civility.

The eventual outcome of the vote was a rejection of a formal ‘no platform’ policy at the university, with just over 1,200 students voting for the option ‘which compelled the Union to adopt a policy of freedom of expression for all views within the law.[66] At the same time, the Education (no. 2) Act 1986 was being passed, which demanded that universities, polytechnics and colleges ‘shall take such steps as are reasonably practicable to ensure that freedom of speech within the law is secured for members, students and employees of the establishment and for visiting speakers.’[67] After seemingly reaching a peak in 1986, the controversy of far right and hard right speakers on university campuses wound down slowly over the next few years (although the issue of ‘no platform’ did not go away entirely).

The University of Bristol seemed to a particular flashpoint for controversy over free speech and the tactic of ‘no platforming’ in the mid-1980s, but was far from alone in witnessing clashes between students and controversial speakers. In recent years, there have been complaints that students today are less open to difficult ideas and are using the policy of ‘no platform’ to silence ideas and speakers that they do not agree with. Looking at the case study of Bristol University in 1985-86, it can be seen that the same criticisms of students were being made then and like today, some commentators have been calling for the enforcement of a policy of free speech protection against a supposedly hostile left on campus.

The ‘no platform’ policy has gained a new notoriety in an era when the far right seems to be making significant strides, with many on university campuses becoming more resistant to encroachment of the far right into their spaces. As scholars like Eric Kaufmann promote ideas that non-white migration has a detrimental effect on host societies and suggest that racist anxieties about immigration are based on legitimate concerns, many feel that this is helping to bring white supremacist ideas to the mainstream and legitimising these ideas through academic discourse. The protest against Kaufmann at Bristol was a response to this, and fits into a much longer history of student protest at the university, whether rightly or wrongly used against various speakers from the right in the 1980s.

Thanks to David Gottlieb for his assistance and feedback on this post.

[1]The Australian, 6 April, 2019, p. 24.

[2]Umut Ozkirimili, ‘White is the New Black: Populism and the Academic Alt-Right’, Open Democracy, 2 January, 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/white-is-new-black-populism-and-academic-alt-right/

[3]Alana Lentin, ‘Beyond Denial: “Not Racism” as Racist Violence’, Continuum, 32/4 (2018) p. 408.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Bristol Post, 5 April, 2019, https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/bristol-university-students-walk-out-2725051.amp

[6]Eric Kaufmann (@epkaufm), twitter thread (https://twitter.com/epkaufm/status/1114473894797299714) , 6 April, 2019.

[7]David Watson & Rachel Bowden, ‘Why Did They Do It? The Conservatives and Mass Higher Education, 1979-97’, Journal of Education Policy, 14/3 (1999) p. 244.

[8]Richard Aldrich, ‘Educational Legislation of the 1980s in England: An Historical Analysis’, History of Education, 21/1 (1992) p. 59.

[9]Leeds Student, 25 January, 1985, p. 1; Leeds Student, 1 February, 1985, p. 3.

[10]Brian Pullan with Michele Abendstern, A History of the University of Manchester, 1973-90(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013) pp. 200-202.

[11]Neil MacMaster, Racism in Europe 1870-2000(Houndmills: Palgrave, 2001) p. 197.

[12][12]Paul Gordon, ‘A Dirty War: The New Right and Local Authority Anti-Racism’, in Wendy Ball & John Solomos (eds),Race and Local Politics(Houndmills: Macmillan, 1990) pp. 184-185.

[13]Ibid., p. 185.

[14]Daily Telegraph, 5 March, 1986, p. 1.

[15]Ibid.

[16]The Times, 28 February, 1986, p. 17.

[17]The Times, 21 June, 1986, p. 8.

[18]The Times, 23 April, 1986, p. 2.

[19]The Times, 10 May, 1986, p. 16.

[20]The Times, 28 May, 1986, p. 1.

[21]House of Commons, Hansard, 10 June, 1986, col. 215.

[22]The Times, 5 September, 1986, p. 2.

[23]Matthew P. Llewellyn & Toby C. Rider, ‘Sport, Thatcher and Apartheid Politics’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 44/4 (2018) p. 579.

[24]Phoenix, 1 May, 1986, p. 1

[25]Daily Telegraph, 26 June, 1986, p. 6.

[26]Times Higher Education, 7 February, 1986, p. 1.

[27]Secretary of State for Education and Science, The Development of Higher Education into the 1990s(London: HMSO, 1985); Times Higher Education, 6 June, 1986, p. 3.

[28]The Times, 26 April, 1986, p. 2.

[29]Ibid.

[30]Daily Express, 26 April, 1986, p. 7.

[31]Camilla Schofield, Enoch Powell and the Making of Postcolonial Britain(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013) p. 330.

[32]‘Speech by the Rt. Hon. J. Enoch Powell, MBE, MP to the Birkenhead Conservative Women’s Luncheon, at the Masonic Hall, Birkenhead, at 1pm, Friday, 20thSeptember, 1985’, PREM 19/1521, National Archives.

[33]Gair Rhydd, 22 October, 1986, p. 1.

[34]Gair Rhydd, 15 October, 1986, p. 1.

[35]Gair Rhydd, 22 October, 1986, p. 1.

[36]Ibid.

[37]Gair Rhydd, p. 2.

[38]Gair Rhydd, 19 November, 1986, p. 1.

[39]Bacus, 3 October, 1986, p. 1.

[40]Ibid.

[41]University of Bristol Newsletter, 16 October, 1986, p. 3.

[42]Ibid.

[43]Ibid., p. 2.

[44]University of Bristol Newsletter, 16 October, 1986, p. 1.

[45]Ibid., p. 1.

[46]Ibid., p. 2.

[47]Bacus, 24 October, 1986, p. 1.

[48]Ibid.

[49]Ibid., p. 2.

[50]Daily Express, 28 October, 1986, p. 8.

[51]Ibid., p. 1.

[52]Socialist Worker, 25 October, 1986, p.

[53]Bacus, 24 October, 1986, p. 2.

[54]Ibid.

[55]Ruth Levitas, ‘Tory Students and the New Right’, Youth and Policy, 16 (1986) p. 4.

[56]Leeds Student, 5 June, 1986, p. 3.

[57]Ibid.

[58]Bacus, 24 October, 1986, p. 12.

[59]Ibid.

[60]Ibid.

[61]Ibid.

[62]Bacus, 7 November, 1986, p. 1.

[63]Ibid.

[64]Ibid., p. 2.

[65]Ibid.

[66]University of Bristol Newsletter, 27 November, 1986, p. 1.

[67]Education (no. 2) Act 1986, s43.

Leave a comment