Anna Chen, prompted by the exclusion of BME workers from Ken Loach’s film The Spirit of ’45, has written in The Guardian that the left seems to be whitewashing the existence of BME from working class history. Chen is right when she argues that the traditional image of the British working class is still white and male and that ‘many on the left would sell us a mythologised, all-white Little England’; however at the same time, when she adds ‘it is worth remembering that the British working class has a proud tradition of rejecting racism’, I would say that this is true from the mid-1970s onwards, but the story of the relationship between Britain’s BME communities and the left and the organised labour movement is much more problematic for most of the 20th century. The left often emphasises its anti-racist credentials and could be accused on whitewashing its treatment of BME workers prior to the 1970s – it might be the case that if BME workers are being excluded from working class history, it is because the left are willing to deal with the less savoury aspects of their interaction with Britain’s migrant communities.

In a 2008 article, Neville Kirk, looking at the inter-war and early post-war periods, argued that the British labour movement ‘adopted a predominantly positive attitude to the issues of immigration and “race”’ and that the scholarly literature has ‘taken far too little account of these expressions of British anti-racism up to the late 1950s’. But for all of the anti-racist rhetoric of the labour movement during this time, the trade unions and its rank-and-file workers were also involved in conflicts with migrant workers. Laura Tabili has shown that white workers in Cardiff and Liverpool, as well as the National Union of Seamen, opposed black and Asian workers being used in British ports and campaigned to controls on their employment in the 1920s. In the early post-war period, the TUC, as well as individual trade unions and the Communist Party, opposed the resettlement and employment of Poles in Britain (particularly in the mining industry). In 1946, the Communist Party produced a leaflet titled ‘No British Jobs for Fascist Poles’ and declared that there was ‘no reason why British jobs should be given to these Poles’. Some, such as Paul Foot and Paul Flewers, have argued that this hostility towards the Poles stemmed from the Stalinism of the CPGB, viewing the Poles in Britain as traitors fleeing the socialist society being formed in Eastern Europe, but doesn’t explain why the TUC and several other trade unions also opposed Polish workers. At the TUC Congress in 1946, the General Council demanded that ‘no Poles should be employed in any grade in any industry where suitable British labour is available’, with a bloc majority of 884,000 voting in favour of this demand.

And it wasn’t just hostility towards the Poles. The CPGB’s Executive Committee member and future leader of the National Union of Mineworkers Arthur Horner declared that his Party ‘would not allow the importation of foreign – Polish, Italian or even Irish – labour’. The TUC itself was, as Beryl Radin described it in 1966, ‘muddled’ in regards to its policies on immigration and ‘race’. Barry Munslow wrote that the general policy of the TUC was to ‘play down the subject, stress the need for immigrants to integrate and oppose special provisions’, while Robert Miles and Annie Phizacklea noted that in the 1950s, the TUC expressed the need for immigration controls, writing that while Congress opposed, on paper, racial discrimination, their position was that ‘immigrants were a problem and their arrival in Britain should consequently be controlled’. Miles and Phizacklea further pointed out that it was until 1973 that a call for the repeal of immigration control legislation was voted in favour for by the TUC General Congress. During the 1960s, the TUC also pushed for colour-blind integration of the workforce and reacted unfavourably to proposed anti-discrimination legislation in employment, such as the sections of employment in the 1968 Race Relations Act. Miles and Phizacklea claim that this reaction ‘at times verged on outright opposition’ and the TUC pushed instead for voluntary conciliation rather than legislative measures.

In his 1986 book, Shattering Illusions, West Indian Communist Party member and trade union activist Trevor Carter (in collaboration with Jean Coussins) wrote that this lack of support for the 1968 Act ‘cannot be put down simply to traditional… union resistance to workplace matters being resolved through the intervention of the law’, but the failure of the trade unions to take the issue of racism seriously. Carter described this position as an issue of putting ‘class before race’ and that issues of racism were subsumed by the wider struggles of industrial militancy and collective bargaining.

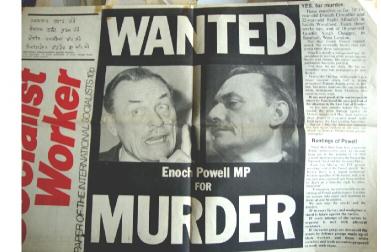

As I have argued here, the Communist Party was probably the progressively anti-racist organisation in the British labour movement from the 1940s to the mid-1960s, but even within this context, BME Party members were, more often than not, sidelined into work for the International Department and rarely included in any decisions made on the Party’s anti-racist policies. But by the late 1960s, the CPGB was unable to take a decisive lead within the labour movement against racism, as shown in the timid approach taken towards the trade unionists that struck in London in favour of Enoch Powell in April 1968 (more of this here and here).

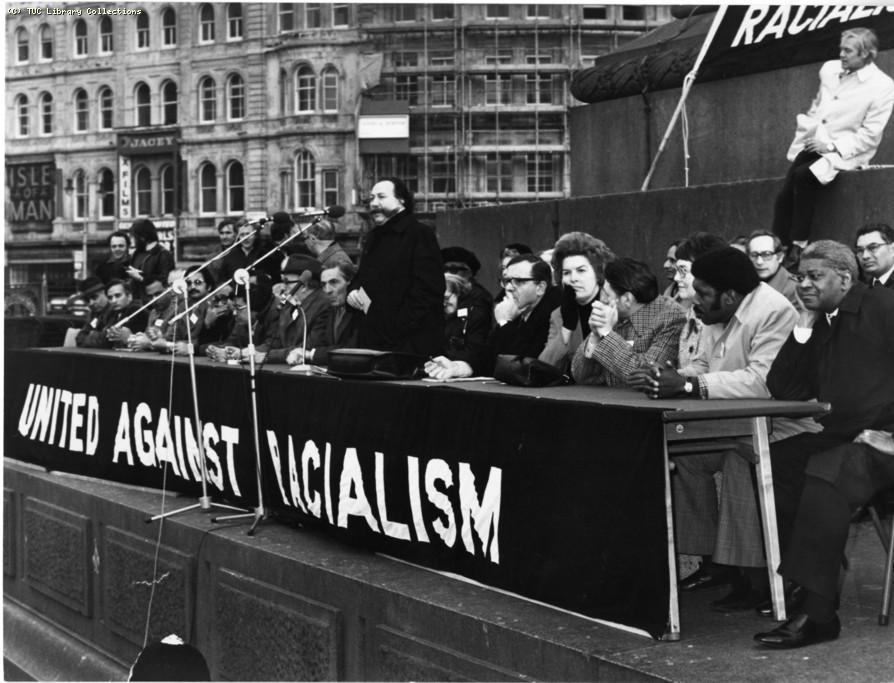

Even into the early 1970s, trade unions were unwilling to tackle racism and refused to assist (and even collaborated with employers in) two strikes involving South Asian workers, the Mansfield Hosiery Mills strike in 1972 and the strike at Imperial Typewriters in Leicester in 1974. The striking workers in both cases felt abandoned by the left and looked to the South Asian communities for material and political support. It was really not until the Grunwick strike of 1976-78 that the aims of BME workers and that of the left and the labour movement converged. But even within the struggle, some BME workers felt that the white trade unionists were there to support the principle of trade union representation, rather than countering the racial discrimination faced at Grunwick. Writing the editorial for Race & Class, A. Sivanandan wrote that the strike was ‘no longer about racism’, but now about the ‘legality… of the weapons that unions may use’ and argued that the structures and tactics of the trade union movement distorted the strike’s objectives, stating that ‘this meant… that instead of directly sabotaging the black workers’ struggle, the [trade union] leaders attempted to contain and incorporate it, clapping a procedure on their backs.’ The use of these procedures, Sivanandan claimed, ‘steered the black workers away from community based support’, which had been key to the strikes in 1972 and 1974.

I have tried to demonstrate in this article that even as the left and the labour movement became more readily involved in anti-racist work, there were some within the BME communities that felt that the left was trying to take over their activism. Balraj Puriwal, the General Secretary of the Southall Youth Movement, started by South Asian youth in the London borough in 1976 in the response to several incidents of racist violence, was quoted as saying, ‘Every time we tried to protest and give our own identity the left tried to take it over… they gave us their slogans and placards… our own identity was subsumed, diffused and deflected’. A Bradford based group of Asian youth, part of the wider Asian Youth Movement across the UK, published a newsletter called Kala Tara, which described this antagonism between the Asian Youth Movements and the leftist groups:

The white left tell us only the working class as a whole will be able to smash racism by overthrowing capitalism and setting up a socialist state. This maybe so, but in the meantime are we, as one of the most oppressed sections of the working class, to sit idly by in the face of mounting attacks. No! We must fight back against the cancerous growth of racism.

Trevor Carter wrote something similar in his book:

My impression was always that the left was genuinely concerned to mobilise the black community, but into their political battles. They never had time to look at our immediate problems, so it became futile to refer to them. So blacks ended up in total isolation within the broad left because of the left’s basic dishonesty.

So the relationship between BME workers and institutions of the British left and the labour movement are more difficult than popularly construed. It is true that the left has a proud anti-racist record in some regards, particularly the long history of the left’s involvement in the fight against fascism, but at other points, the left has ignored or downplayed the problems faced by BME people in Britain.

More info can be found here: http://www.unionhistory.info/britainatwork/narrativedisplay.php?type=raceandtradeunions

EDITED TO ADD: Anna has posted her piece at her blog with links to other relevant pieces, including this post.

Leave a reply to hatfulofhistory Cancel reply